Carpenters Spearheaded the Movement for Shorter Work Hours

Many union members know it is the labor movement that brought big improvements for workers over many decades. Child labor laws, breaks during the workday, overtime pay and weekends without work are just a few examples.

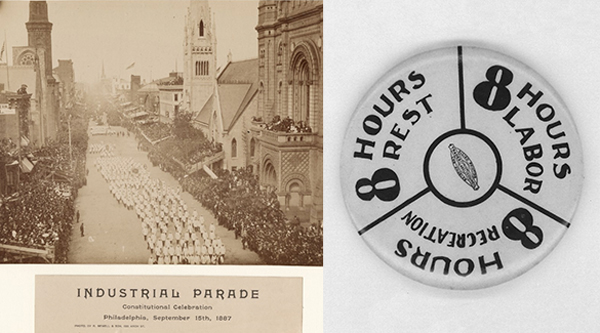

Another is the eight-hour day—the pillar of our working and family lives and a foundation of the middle class. We would not have this basic protection without decades of struggle by workers and the unions that came to represent them, led by the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, which later added ‘United’ to its name to become the UBC.

Carpenters were among the earliest to lead workers agitating for relief from 12-hour workdays that threatened their safety and health and stole away time from family and rest.

One of the earliest strikes to win the 10-hour day occurred among Philadelphia carpenters in 1791. That same decade, journeymen carpenters organized in cities including New York, Carlisle, PA; Halifax, NS; Savannah, GA; and Boston.

In the mid-1830s, the Philadelphia building trades again went on strike and on October 24, 1836, the Philadelphia Association of Journeymen House Carpenters organized a national convention of carpenters with the 10-hour-day campaign as its theme.

On March 31, 1840, President Martin Van Buren finally issued an executive order establishing the 10-hour day on all government projects. It was an important milestone, but the agitation continued as workers organized while new industries and technology advanced after the Civil War. Shorter-hours efforts also were central in Canada. Hamilton, ON, carpenters won the nine-hour day in 1872 and early Halifax ship caulkers also won a shorter-hours fight.

Wealthy employers used their power to fight back, often violently, when workers took to the streets. And economic recessions repeatedly wiped out the gains that organized workers made. Still, the ten-hour movement shifted to become a campaign for the eight-hour day—and carpenters again led the way.

Our Brotherhood was founded at a Chicago convention of 36 carpenters on August 12, 1881. Among the officers elected were two eight-hour-day activists: Gabriel Edmonston, the union’s first president—and Peter J. McGuire, our founding general secretary.

Edmonston opposed depending solely on legislative change and pushed for decisive action on shorter hours, advocating for workers to “establish reforms…ourselves.” He won a motion at the Federation of Organized Trades meeting in 1884 when delegates resolved “that eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labor from and after May 1, 1886.”

On that May Day, 1886, more than 190,000 workers struck for the eight-hour-day.

McGuire, whose passion and energy laid the foundation for the building of our union—carpenter to carpenter, town to town—added a moral dimension to the practical needs of workers seeking shorter hours.

As he told an audience at Boston’s Faneuil Hall in 1886:

“This labor agitation is not, as some imagine, the rantings of a howling mob, nor is it simply a struggle to get possession of more grub. It is a struggle to secure an opportunity for physical, mental and moral improvement among the people, and the eight-hour movement is the entering wedge.”

By 1900, carpenters in 186 cities and towns were working under the eight-hour rule.

The U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act, passed in 1937 during the Great Depression, helped establish the eight-hour day among most U.S. workers by mandating overtime pay after a 40-hour workweek. The Canada Labour Code, including work hours regulations, was enacted in 1968.

These standards still come under threat regularly and we agitate and organize to preserve them through our political and legislative work.

It’s part of our legacy.

Source: The Road to Dignity: A Century of Conflict (History of the UBC 1881-1981) by Thomas R. Brooks.